Food Waste: State of the Market, Challenges, and Opportunities

A tale of energy density, a fragmented market, and the limitations of transporting matter.

For the past few months, I’ve had the pleasure to dig into the food waste industry with an awesome team, under the guidance of Dave Danielson and Joel Moxley.

Food waste is a largely unsolved and fascinating problem space. As Ryan Petersen, CEO of Flexport, said about the global freight industry, “where there’s mystery, there’s margin” (originally attributed to Poor Charlie’s Almanack).

The same thing applies to the food waste industry.

While there are many challenges and hurdles, I’m optimistic they can be overcome, and that huge GHG reductions, white space, strong moats, and venture-scale growth are waiting to be unlocked on the other side.

In this post, I will lay out everything my team and I learned during our investigations. We focused specifically on food waste in California — I’ll go into more detail later as to why. In this post, I will cover:

- The conundrum of food waste

- America’s food waste problem

- State of the market

- Why now?

- Challenges

- Opportunities

First, a word about teams

My team’s exploration of food waste was one of the most intense, productive, and fulfilling projects I’ve worked on. And my biggest takeaway was not about the industry or the market, but rather a deep appreciation of the importance of the people.

I worked with a kickass team, and we would have gotten nowhere close without the people. VC’s often talk about the importance of the team, and while I understood this on a conceptual level, it wasn’t until I went through this experience firsthand that I believed this on a deep, visceral level. The people matter, and I couldn’t have done it without them!

Now let’s talk food waste.

The Conundrum of Food Waste

The story of food waste is the story of a highly diffuse resource with low energy density.

In this sense, food waste is similar to the early days of the solar and wind industries. One of the most memorable quotes I’ve heard about wind energy is “The wind is free. You just have to pay for everything else.”

What do you do when you have a valuable resource, but it costs more to harvest the resource than it’s worth?

This brings us to the conundrum of food waste: it has inherent value — it contains nutrients that can be converted to fertilizer, and consists of organics that can be converted into biogas, which can be used for renewable heat or electricity. But the energy content is so diffuse that the cost of moving it around often exceeds its value.

As one of my mentors put it aptly, it costs more to move matter than heat or electrons. This is the core challenge with food waste — you can grind it up, dry it, divert it, or do any number of things with it, but at the end of the day, it’s expensive to move atoms.

Hermione: “It’s impossible to make good food out of nothing! You can Summon it if you know where it is, you can transform it, you can increase the quantity if you’ve already got some…”

In the world of Harry Potter, you can’t make good food out of nothing. Similarly, in our world, you can’t turn food waste into nothing.

America’s Food Waste Problem

The problem with food waste boils down to one word: methane. When organic material breaks down under anaerobic conditions, which occurs in landfills, it generates methane, which is a greenhouse gas ~25x more potent than carbon dioxide.

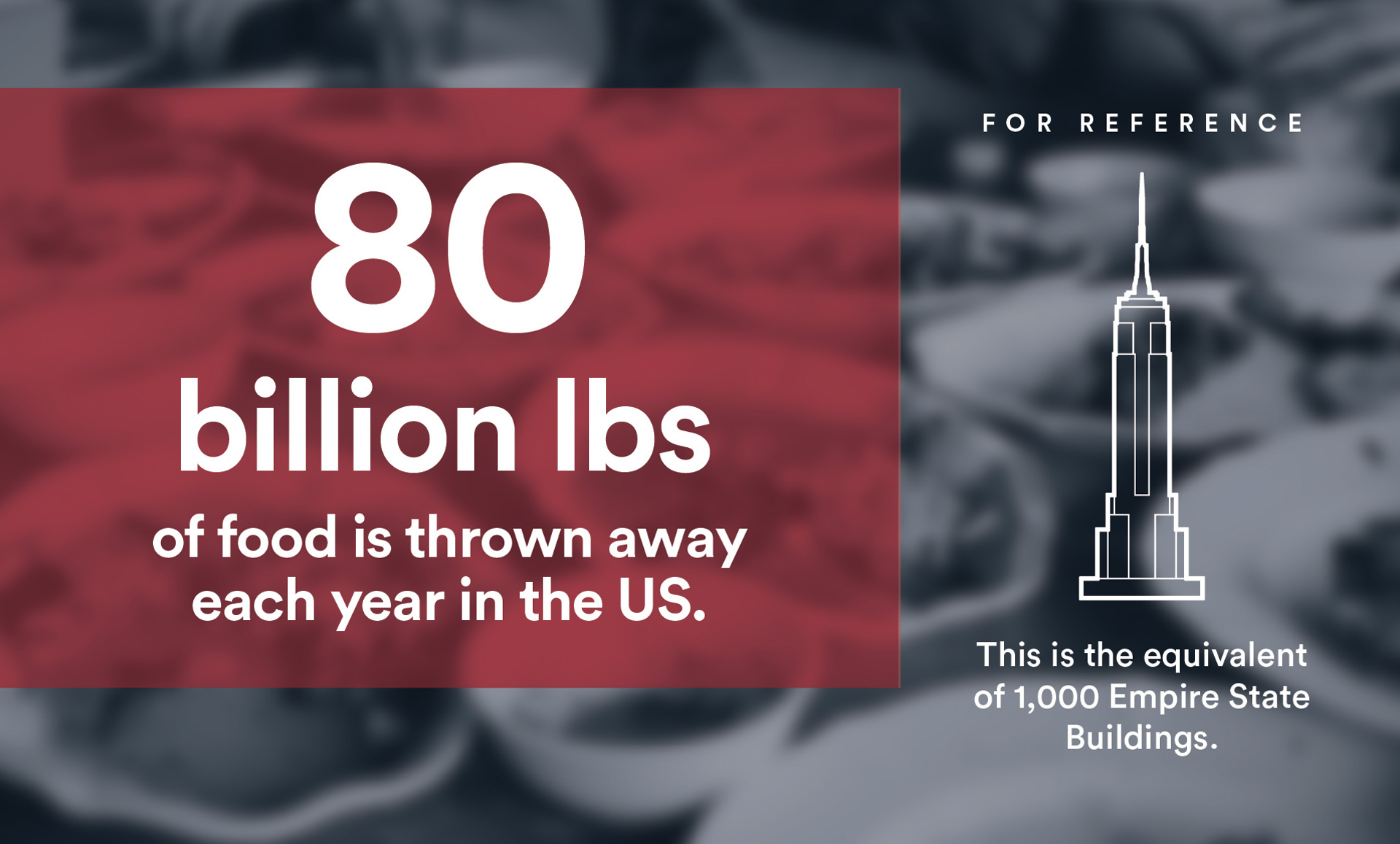

A few facts illustrate the magnitude of this problem:

- 40% of the food waste in the US goes to waste

- $130 billion worth of food is wasted annually

- 23% of US methane emissions are from landfilled food waste

We mainly hear about methane from agriculture, livestock, and the oil and gas industry, but almost a quarter of US methane emissions stem from organic material in landfills.

Note that this problem applies not only to food waste, but other types of organic waste as well, such as yard trimmings, brush, animal bedding, and a few other miscellaneous categories.

State of the Market

The food waste industry is a complex system that is highly fragmented, localized, and filled with bespoke contracts. The industry consists of a few different parties: food waste producers, haulers, waste processors, and regulators.

Waste Producers

We started out by mapping out the landscape for waste producers. These are the businesses we’re most familiar with. A few examples include:

- Dining halls–at universities, hospitals, etc.

- Grocery stores

- Malls

- Restaurants

- Households

- Distribution centers

Excluding farms, the share of food waste attributed to each producer category is roughly as follows:1

- Households — 45%

- Restaurants — 33%

- Grocery stores — 10%

- Other institutions (hospitals, universities, municipalities, etc.) — 10%

- Food processing facilities — 2%

We saw this list and naturally focused on the combined ~80% share from households and restaurants. However, we quickly realized these were also the hardest categories to tackle.

To understand why, it’s helpful to think about the factors that determine the value of a food waste stream:

- Amount of waste produced: A college dining hall that produces 5 tons/day at one location is a more attractive potential customer than a hundred single-family homes that produce the same amount of waste in aggregate. This goes back to the idea of energy density.

- Contamination: The industry distinguishes between pre-consumer and post-consumer food waste, which is pretty much what it sounds like. Pre-consumer food waste, such as kitchen scraps, are generally lower contamination than post-consumer food waste, which is more likely to contain cutlery, napkins, and other non-organic waste. Contamination matters for certain types of waste processing facilities more than others — I’ll go into more detail in the next section.

Regrettably, out of all the food waste producer categories, household food waste has the lowest energy density and largest degree of contamination. We didn’t run a detailed techno-economic analysis, but I would bet that it’d be excruciatingly difficult to make the economics work here.

Restaurants produce more food waste, but they are low-margin businesses. They generally do not produce large amounts of pre-consumer food waste, because any wasted food is lost revenue. As a result, a large fraction of restaurant food waste is post-consumer, which tends to be higher in contamination.

Ultimately, we decided to focus our efforts on grocery stories and MUSH institutions (municipalities, universities, schools and hospitals).

Haulers

Haulers play a central role in this ecosystem, and they have a lot of power. The main haulers are Republic Services and Waste Management, but there are many other smaller businesses that are more localized. Besides the major players, hauling is a fragmented industry, and from our initial conversations, we suspect there’s a long tail distribution of haulers.

Bigger haulers generally also own and operate waste processing facilities, while smaller haulers will partner with waste processing facilities and only handle the transportation.

I had assumed that haulers who also own waste processing facilities would prioritize bringing waste to their facilities, which would yield additional revenue from the tipping fee (A tipping fee is the industry term for the amount you pay a waste processor for receiving your waste, generally charged per ton). It turns out this is not always the case.

Hauling is also a low-margin business, and hauling costs correlate with distance travelled due to fuel and labor costs. Haulers are incentivized to bring waste to the closest waste processing facility, even if it’s a competitor’s facility. Even the gorillas of the industry, Republic Services and Waste Management, do this. In fact, more money is made from hauling food waste than from receiving a tipping fee at a waste processing facility.

This was a shocking realization for us, but it reiterated that the diffuse nature of food waste and the cost of moving atoms are fundamental concepts in the industry.

All players in the industry, and all decisions that are made, must take into account these realities, and if you’re going to think about food waste, you have to view the world through this lens. If it weren’t such a vexing methane problem, it would be quite an elegant marriage of free markets and physics.

Waste Processors

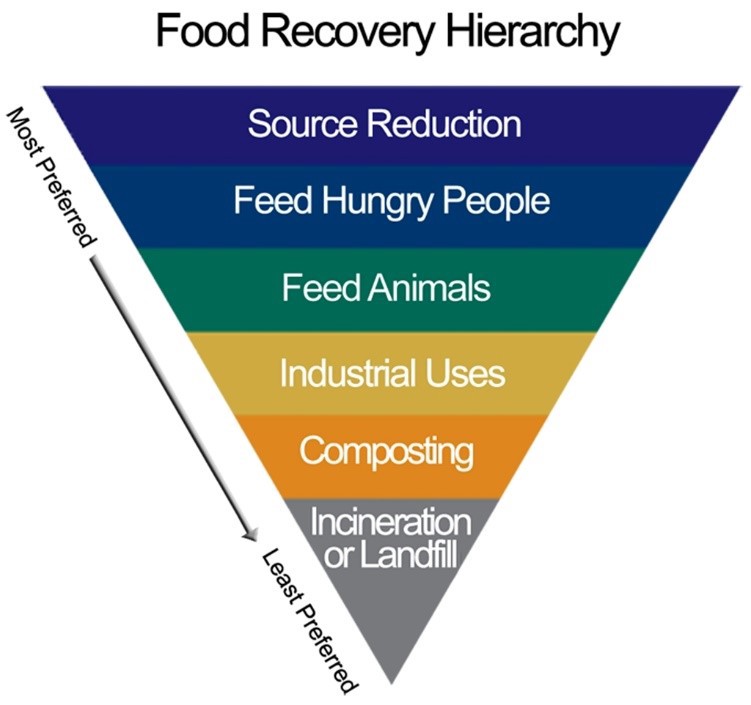

When thinking about waste processors, it’s helpful to frame the topic with the EPA’s food diversion hierarchy:

In short, don’t burn or landfill your waste if possible.

From an ethical standpoint, the best way to reduce food waste is to produce less food, then to divert unused food to people. These are admirable goals, but source reduction and food diversion are not always possible, and animal feed is smaller in scale, so we set our sights on understanding the next two categories: industrial uses (mainly anaerobic digestion) and composting.

One thing to keep in mind is that because of the cost of transportation and the fact that food waste is time-sensitive (i.e. it will smell, leak, and potentially attract rodents), in all of these cases, the waste producer pays the waste processor, even if you’re giving unused food to a food bank, or edible food to an animal feed facility.

Anaerobic digestion: On paper, anaerobic digestion (AD) sounds like a miracle technology. Dump food waste in a controlled environment with methanogens (a type of bacteria that convert organic matter into methane), and you can generate biogas (used for heating or electricity), fertilizer, and even clean water.

In reality, AD is a difficult technology to execute. It’s only economical at scale, so AD plants require high capex, and contamination in the waste stream can shut down the entire system. Harvest Power was a hot VC-backed startup that owned and operated AD facilities, but it shut down in 2019.

One of the challenges with AD is that it does not reduce the volume or mass of the waste stream. The material that comes out of an AD facility, called digestate, still needs to be processed, and the AD facility often pays to send it to a composting facility.

This begs the question, why not just use a composting facility in the first place? The answer is based purely on the economics — compared to a composting facility, an AD gives you renewable heat and/or electricity, but at the cost of much higher capex, maintenance, and complexity.

And if you’re trading a costly facility for renewable energy, why not just build a (much cheaper) composting facility and install rooftop or community solar with a PPA? I want to believe in AD, but I haven’t found a convincing argument so far.

Composting: A composting facility breaks down organic waste aerobically, so CO2 is produced instead of methane If we’re splitting hairs, composting can generate small amounts of methane and nitrous oxide if the operation is not managed well, but there’s a significant GHG benefit compared to landfills. The resulting compost is nutrient-rich, and can be sold to farmers as fertilizer.

Landfills: The vast majority of our waste ends up in a landfill. Landfills are by far the cheapest option, and they are the most widespread. Because food waste is expensive to transport, waste is typically solutions are typically very localized.

From a GHG standpoint, the goal is to minimize organic waste that ends up in a landfill. While some landfills capture and recover methane, this is still a relatively small fraction.

Why Now?

Everything I’ve described so far has been the case for a while. So why now? The answer is California. Specifically, the main drivers are Senate Bill (SB) 1383, the low carbon fuel standards (LCFS), and increasing tipping fees.

SB-1383

SB-1383 is a new piece of legislation slated to go into effect in January 2022. It mandates that jurisdictions and municipalities must have a plan in place to divert organic waste from landfills.

Food waste is a legacy industry that’s fragmented and obscure, with a lot of bespoke contracts and partnerships. From our market research and customer interviews, we believe SB-1383 will be the catalyst that pushes gears into motion.

I’ll go into more detail in the Opportunities section, but for startups interested in tackling this space, SB-1383 provides the perfect timing to create a more transparent free market in the waste industry.

Low Carbon Fuel Standards

LCFS credits are given to projects that generate renewable natural gas. This mainly applies to AD facilities, and it adds significant revenue beyond market prices for gas.

Increasing Tipping Fees

Along with Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, California has among the highest tipping fees in the country, and they’re increasing. This is largely driven by supply and demand — the amount of land area is fixed, so new landfill capacity will increasingly be built in less accessible, less desirable locations, driving up costs.

Challenges

I touched upon some of these earlier, but here’s a list of challenges with food waste, as well as the broader industry dynamics:

- Cost of moving atoms — Food waste has inherent value, but the cost of transporting it often exceeds the value

- Localized — Because it’s costly to transport food waste, the industry is very localized. Haulers want to minimize the distance between the waste producer and waste processor, which limits the number of options.

- Distributed resource — Food waste is a diffuse resource, which make sit costly to collect, transport, and sort

- Contamination — A pure organic waste stream is valuable for composting and AD facilities, but most waste streams have some degree of contamination that can cause trouble for these facilities. There are material recovery facilities, which can sort contaminated waste streams, but these are costly.

- Time-sensitive — Food waste has a shelf life. If it’s not collected for too long, there may be odor, leakage, and rodents, which result in headaches and/or fines for waste producers.

- Out of sight, out of mind — Waste producers such as restaurants and grocery stores do not want to deal with food waste. It’s not part of their core business, and they would like nothing better than for someone else to handle it for them.

- Fragmented industry — Aside from a few examples, the waste industry has not seen a large degree of innovation. It’s a relatively relationship-based industry, with bespoke contracts and low degree of standardization. We often heard drastically different things from our customer discovery calls from one day to another.

Opportunities

That being said, I also believe that there is ample opportunity in this space. Here are a few areas I would look for potential newco opportunities. While they may not be the right ideas, as Paul Graham said, most fairly good ideas are adjacent to even better ones, so I hope this provides a useful starting point.

Distributed solutions that can treat or process food waste at the source.

There are a few examples here, but the idea that we felt was most promising was to use devices to reduce the weight and volume of food waste on-site. Our key insight was that food waste is costly to transport, but we’re sitting on top of well-established infrastructure for liquid waste: the drainage system.

Macerators are devices that pulverize food waste so that it can be sent down the drain. The challenge here is that this drastically increases total suspended solids (TSS) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) of the water, which may result in a surcharge from the local water treatment plant.

Pulpers and extractors are devices similarly grind up food waste, but instead of sending it down the drain, they remove water from the waste stream. Overall, this can reduce the weight of food waste by 50–80%, which saves hauling fees for the waste producer.

Marketplace for Food Recovery

Through SB-1383, California set an ambitious goal of recovering 20+% of edible food (the exact definition of what can be recovered is still up in the air). Food recovery is localized and time-sensitive, and may benefit from the scale of a marketplace that matches supply and demand. Food For All is tackling this space, but has not achieved meaningful scale.

Inventory Management and Analytics

One of my mentors has a saying that when you’re trying to sell energy savings to consumers, you should focus on anything but the energy. Rather, focus on things people care about instead, such as comfort (Nest) or status (Tesla).

The same idea may apply to food waste. Instead of focusing on the waste, follow the trail of revenue, which in the case of grocery stores, leads to inventory management and reducing wasted inventory. There are a few startups tackling this space, including Afresh and JAMIX.

Digitization / Compliance Reporting

The area I’m most intrigued by is the digitization of the waste industry. Similar to how Flexport developed a standard for freight forwarders to improve transactions and record-keeping, there’s an opportunity to streamline operations among waste producers, haulers, processors, and regulators.

SB-1383 provides a promising catalyst, since new regulations will require long-standing contracts to be revisited and updated. Additionally, stricter rules will require more effort to be invested in compliance reporting, which is currently a manual and time-consuming process. To our knowledge, Rubicon is the company that’s most similar to this idea, but there aren’t any startups directly addressing this space.

Final Thoughts

To sum up, the food waste industry faces unique challenges, but I believe they are all solvable problems with opportunity on the other side.

The industry is localized, fragmented, and defined by relationships. As such, we think there’s white space for data and greater transparency in the marketplace.

Food waste as a physical product is a diffuse resource that has a “shelf life” (odor, rodents, etc.) and is costly to move.

I believe there’s opportunity for decentralized solutions to reduce cost, but any prospective solutions must keep in the volume of the waste stream and the degree of contamination. Thus, solutions that address large point sources (e.g. distribution centers, college dining halls) are more economical and easier to execute than distributed sources (e.g. single family homes).

Notes

-

From our research, people generally exclude food waste from farms because any crops that can’t be sold are typically not harvested or composted on-site. It’s hard to find a cheaper alternative to doing nothing! ↩